Overview of Euripides’ Medea

Euripides’ Medea, originally produced in 431 BCE, is a powerful tragedy centered on Medea, a woman grappling with betrayal after her husband, Jason, abandons her. The play explores themes of revenge, the plight of women, and cultural clashes. It is a cornerstone of classical Greek literature.

Synopsis of the Play

The play opens with Medea, wife of Jason, consumed by grief and rage after Jason abandons her and their children to marry Glauce, the daughter of Creon, King of Corinth. Medea, a barbarian princess and sorceress, laments her fate and plots revenge against Jason for his betrayal.

Creon, fearing Medea’s potential for retaliation, orders her into exile. Medea begs for one day to make arrangements for her departure and secure the future of her children. Creon grants her request, unaware of the deadly plan she is concocting.

Medea feigns compliance and sends her children with poisoned gifts—a robe and a crown—to Glauce. Glauce and Creon both die after putting on the gifts. Medea then completes her revenge by murdering her own children, denying Jason any future lineage. She escapes in a chariot given by her grandfather Helios, leaving Jason devastated and alone, forever haunted by his actions and her vengeance.

Major Themes in Medea

Medea explores the destructiveness of revenge, the unfair treatment of women in ancient Greek society, the clash between barbarian and Greek cultures, and the constant threat of exile. These themes intertwine to create a complex tragedy.

Revenge and its Destructiveness

Revenge is a central, devastating force in Medea. Spurned by Jason, Medea seeks vengeance not only on him but also on those connected to his betrayal. Her actions are driven by a profound sense of injustice and a burning desire to inflict pain equal to her own suffering.

Medea’s revenge transcends typical anger; it becomes a calculated, merciless campaign. She meticulously plans and executes acts that maximize the emotional and social damage, demonstrating a chilling level of control over her rage. The consequences of her revenge are far-reaching and catastrophic.

The play highlights how revenge consumes the revenger. Medea’s pursuit of vengeance leads her to commit unspeakable acts, ultimately destroying herself and everything she holds dear. The destructiveness of revenge is evident in the complete annihilation of familial bonds and the profound psychological toll it takes on Medea, leaving her isolated and broken.

The Plight of Women in Ancient Greek Society

Medea vividly portrays the precarious position of women in ancient Greek society. Medea, as a foreign woman in Corinth, experiences firsthand the limitations and vulnerabilities imposed upon her gender. She lacks political power, legal rights, and social standing, making her dependent on her husband for security and status.

The play underscores the double standards prevalent in ancient Greece, where men enjoyed freedoms denied to women. Jason’s infidelity and abandonment of Medea highlight the lack of recourse available to women in such situations. They were often treated as property, subject to the whims and desires of their male counterparts.

Medea’s passionate speeches articulate the frustrations and injustices faced by women, revealing their limited options and the societal pressures that confine them. Her desperate actions can be interpreted as a rebellion against these constraints, a desperate attempt to reclaim agency and assert her worth in a world that devalues her.

The Clash Between Barbarian and Greek Cultures

Medea explores the tensions between Greek civilization and what the Greeks considered “barbarian” cultures, represented by Medea’s Colchian origins; Medea’s foreignness sets her apart in Corinth, making her an outsider and contributing to her vulnerability. The Greeks often viewed non-Greeks as less civilized and more prone to irrationality, a stereotype that impacts how Medea is perceived.

Medea’s use of magic and her passionate nature are characteristics that the Greeks might have associated with barbarian cultures, further emphasizing the cultural divide. This clash contributes to the misunderstandings and prejudices that fuel the tragedy. The play questions the perceived superiority of Greek culture and highlights the dangers of xenophobia.

Furthermore, the play challenges the audience to consider whether the Greeks’ rigid social structures and patriarchal norms are truly more civilized than the values of other cultures. Medea’s actions, though extreme, can be seen as a response to the limitations imposed upon her by Greek society, prompting a reevaluation of cultural biases.

The Theme of Exile

Exile is a prominent theme in Medea, highlighting the vulnerability and precariousness of individuals without a secure place in society. Medea, as a foreigner in Corinth, experiences a form of exile even before Creon formally banishes her. Her lack of social and political connections makes her dependent on Jason, and his betrayal leaves her utterly exposed.

The threat of exile hangs over Medea, fueling her desperation and contributing to her vengeful actions. Exile represents a loss of identity, security, and community, forcing individuals to navigate unfamiliar and often hostile environments. Medea’s fear of being cast out and left with nothing amplifies her sense of injustice and drives her to extremes.

Furthermore, the play suggests that exile can be both a physical and a psychological state. Even within Corinth, Medea remains an outsider, disconnected from the social fabric and unable to fully integrate. This sense of alienation contributes to her feelings of rage and fuels her desire to strike back at those who have wronged her, solidifying the theme.

Character Analysis

Medea presents complex characters driven by powerful emotions and societal pressures. Medea, Jason, and Creon each embody distinct motivations, contributing to the play’s tragic unfolding and exploring themes of betrayal, ambition, and the clash of cultures.

Medea⁚ The Powerful Enchantress

Medea, the titular character of Euripides’ tragedy, is a figure of immense power, driven by a potent combination of intellect, passion, and magical abilities. As a Colchian princess and a sorceress, she wields knowledge and skills that set her apart from the Corinthian society she inhabits. Her barbarian origins further contribute to her otherness, making her both feared and misunderstood. Medea’s love for Jason is all-consuming, leading her to betray her own family and homeland to aid him in his quest for the Golden Fleece. When Jason abandons her for Glauce, Creon’s daughter, Medea’s love transforms into a burning desire for revenge.

This desire fuels her actions throughout the play, culminating in the horrific murder of her own children. Medea’s capacity for both intense love and brutal violence makes her a deeply complex and disturbing character. She is not merely a victim; she is an active agent, wielding her power to exact retribution on those who have wronged her. The play delves into the depths of her psyche, exploring the motivations behind her choices and the consequences of her relentless pursuit of vengeance, solidifying her as a captivating figure.

Jason⁚ The Betrayer

Jason, the celebrated hero of the Argonauts, stands in stark contrast to Medea in Euripides’ play. While initially presented as a figure of heroic stature, Jason’s actions reveal a self-serving and ultimately cowardly character. He abandons Medea, his wife and the mother of his children, to marry Glauce, the daughter of Creon, King of Corinth. This act of betrayal sets in motion the tragic events of the play. Jason justifies his decision as a pragmatic move to secure a better future for himself and his children, claiming that his marriage to Glauce will provide them with social and financial stability.

However, his arguments ring hollow, revealing a lack of empathy and a disregard for Medea’s sacrifices. He fails to recognize the depth of her love and the extent of her devotion, dismissing her as a “barbarian” woman who should be grateful for the opportunities he has provided. Jason’s pursuit of personal gain blinds him to the devastating consequences of his actions, ultimately leading to the destruction of his family and the loss of everything he holds dear. His character serves as a foil to Medea’s, highlighting the destructive nature of ambition and the betrayal of trust.

Creon⁚ The King of Corinth

Creon, the King of Corinth, plays a pivotal role in Euripides’ Medea as the catalyst for the tragic events that unfold. He is portrayed as a cautious and pragmatic ruler, primarily concerned with the stability and security of his kingdom. His decision to banish Medea stems from his fear of her potential for revenge, recognizing her powerful intellect and her capacity for extreme actions. He sees her as a threat to his daughter, Glauce, and to the stability of his reign, and therefore believes that banishment is the only way to protect his kingdom.

Creon’s actions, while seemingly justified by his concern for his people, ultimately contribute to the tragedy. His decree of exile forces Medea into a corner, driving her to commit unspeakable acts of revenge. While he attempts to reason with Medea and offers her a day’s reprieve before her banishment, his underlying fear and distrust are evident. He fails to understand the depth of Medea’s pain and the extent of her desperation, ultimately underestimating the power of a woman scorned; Creon represents the political pragmatism that clashes with Medea’s passionate and vengeful nature.

Interpretations and Scholarly Debate

Euripides’ Medea has been the subject of extensive interpretation and scholarly debate for centuries, with critics offering diverse perspectives on the play’s themes and characters. One central point of contention revolves around Medea’s motivations and the extent to which her actions are justified. Some scholars view her as a victim of patriarchal society, driven to infanticide by Jason’s betrayal and the lack of agency afforded to women in ancient Greece. This perspective emphasizes the social injustices that fuel her rage and desperation, portraying her as a symbol of female rebellion against oppressive forces.

Conversely, other interpretations focus on Medea’s barbarity and her willingness to commit unspeakable acts to achieve her revenge. These scholars argue that her actions are morally reprehensible, regardless of the circumstances, and that she embodies the destructive potential of unchecked passion and the dangers of foreign influence within Greek society. The debate also extends to the interpretation of Jason’s character, with some critics viewing him as a pragmatic opportunist and others as a victim of his own ambition and societal expectations.

Medea’s First Production and Reception

Medea was first presented at the City Dionysia in Athens during the spring of 431 BCE, a significant annual festival dedicated to the god Dionysus. Euripides’ play was part of a dramatic competition that included works by other playwrights. Interestingly, despite its enduring fame and powerful impact, Medea did not win the competition; it only received third prize. This initial reception suggests that the play’s themes and characters were, perhaps, too controversial or unsettling for the Athenian audience of the time.

The play’s unflinching portrayal of a woman driven to infanticide likely challenged prevailing social norms and expectations regarding female behavior. The character of Medea, a barbarian woman who defies Greek conventions, may have been seen as a threat to the established order. Furthermore, the play’s exploration of complex moral issues and its ambiguous depiction of justice may have left the audience feeling uneasy. While the exact reasons for its initial reception remain debated, it is clear that Medea provoked a strong reaction and sparked discussion among its first viewers.

Translations and Adaptations of Medea

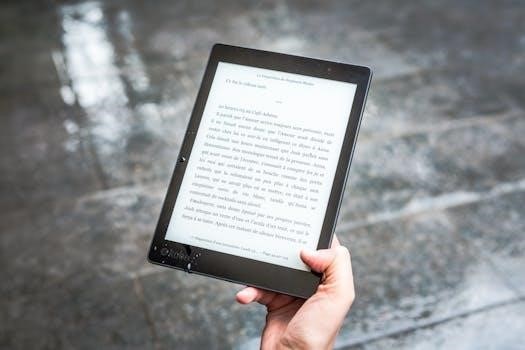

Euripides’ Medea has resonated across centuries and cultures, inspiring countless translations and adaptations in various forms. From faithful renderings of the original Greek text to bold reinterpretations, the play’s enduring power has captivated artists and audiences alike. Numerous English translations exist, catering to different preferences, from those seeking scholarly accuracy to those desiring a more accessible and poetic reading experience. Notable translators include E.P. Coleridge, Gilbert Murray, and more recently, individuals and teams dedicated to revitalizing the text for modern audiences.

Furthermore, Medea has been adapted into plays, operas, novels, and films, each offering a unique perspective on the story’s themes and characters. Robinson Jeffers’ adaptation is particularly well-known for its powerful language and dramatic intensity. These adaptations often explore specific aspects of the play, such as the psychological complexities of Medea or the social injustices she faces. The continued interest in translating and adapting Medea demonstrates its timeless relevance and its ability to spark new interpretations across generations.

The Medea Complex

The “Medea complex” is a psychological term derived from Euripides’ play, referring to a parent’s desire to harm their own children as an act of revenge against their spouse or partner. This concept, explored in scholarly articles and psychological analyses, delves into the extreme emotions of betrayal, abandonment, and rage that can drive a parent to such a devastating act. While the play depicts Medea’s infanticide as a response to Jason’s infidelity, the “Medea complex” is not limited to cases of infidelity alone.

It can arise from various forms of parental alienation, custody battles, or deep-seated psychological issues. It’s crucial to note that the “Medea complex” is a complex and rare phenomenon, distinct from everyday parental anger or frustration. The concept has been explored in literature, film, and academic studies, prompting discussions about the psychological factors that can contribute to such extreme acts of violence and the potential for early intervention and prevention. This exploration allows one to understand the darker aspects of human emotion.

Sources and Further Reading

For those seeking deeper insights into Euripides’ Medea, numerous resources are available. Primary sources include the original Greek text, often accompanied by English translations and scholarly annotations, such as those by E.P. Coleridge and Gilbert Murray. Secondary sources offer critical analyses of the play’s themes, characters, and historical context. Academic journals and books, such as those edited by D. Stuttard, provide diverse interpretations and scholarly debates surrounding Medea.

Furthermore, exploring works on Euripides’ life and the social context of ancient Greece can enrich understanding. Resources like encyclopedia entries on Medea and Jason, as well as analyses of themes like revenge and the status of women, offer valuable perspectives. Additionally, examining adaptations and translations of Medea across different time periods can reveal the play’s enduring relevance. These resources can be accessed through university libraries, online databases, and reputable booksellers. Exploring these sources can provide a comprehensive exploration.